Truth Decay

Every year, the founder of the Non-Obvious Company, Rohit Bhargava, offers a series of predictions for major trends that will impact our world. Bhargava is an author, entrepreneur, and former marketing strategist, and as his company’s name suggests, he has forged a reputation for seeking out the non-obvious trends that may be on the horizon.

This year, he presented some of these predictions at the virtual South by Southwest festival. I recommend checking out the entire talk, but one that seemed especially prescient was #3: We are in the midst of a deep believability crisis.

That tracks right along with a recent Vox interview with Jennifer Kavanagh, senior political scientist at the Rand Corporation. Kavanagh is studying “truth decay” or our inability to agree on common facts and trust in shared institutions.

For both Bhargava and Kavanagh, when reality and facts become debatable, it’s impossible to know who to trust. Company’s use phrases like “all-natural” to describe processed foods that fit a loose legal definition. Politicians and media sources promote different realities with competing sets of “facts”. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, Pew surveys show less than half of Americans describe news media as “largely accurate” and about a third say that news media’s coverage of COVID-19 is actually hurting the country.

The Age of Mistruths

In some ways, it’s not surprising that we are where we are. The spread of viral content online has been an attractive opportunity for both foreign adversaries and unscrupulous publishers. A study from Standford University, published in 2016, surveyed more than 7,000 students across 12 states, from well-funded suburban schools to struggling urban districts. They found that many American young people, regardless of geography, affluence, or grade level, lack the ability to critically evaluate information online.

Obviously, these young people turn into American adults, so there’s little reason to believe that when so-called “digital natives” struggle to critically evaluate claims online that older generations will do any better.

This trend was famously targeted during the 2016 election by Russia. Arguments can be made about the real impact of the meddling, but U.S. intelligence services have consistently confirmed Russian interference and thousands of Russian-backed ads and bot accounts have since been identified.

Perhaps slightly less malicious, foreign media groups have also sought to exploit America’s susceptibility to fake news by churning out exaggerated and outright false articles from content farms. The goal is maximum virality to drive engagement and clicks, and thus ad revenue. So the more outlandish and enraging the article is, the more people will share.

Couple bad actors with the famous adage “a lie can get halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes”, and it’s no surprise we’re where we are. The NY Times detailed one such example of a single tweet, by a private citizen with few followers, turning into a national phenomenon literally overnight. From Reddit to Facebook to online “news” sites with little to no editorial oversight to political commentators hoping to inflame outrage, all the usual suspects were involved. And no amount of clarifications, corrections, or statements from the people actually involved could quell the fire.

And of course, we can’t discuss the era of fake news without including Donald Trump. As a frequent spouter of false claims, a spreader of misinformation online, and someone who often labels any critical coverage as “fake news”, the current U.S. President is entangled in the post-truth era in a powerful way.

An upcoming book from The Washington Post’s Fact Checker team details more than 16,000 falsehoods from the 45th President of the United States in his first term. Though the frequency of falsehoods is growing year by year, that number averages out to a handful of lies every day since the start of his presidency.

Not a new problem

Here’s our real challenge, though. This isn’t a new problem, and it can’t be solved with a single election.

Even during the 2016 election, 81% of registered voters said that Republicans and Democrats could not agree on basic facts. Ironically, it was a rare instance where both sides of the aisle agreed that they couldn’t agree. And our trust in government, media, and even one another has been declining for years.

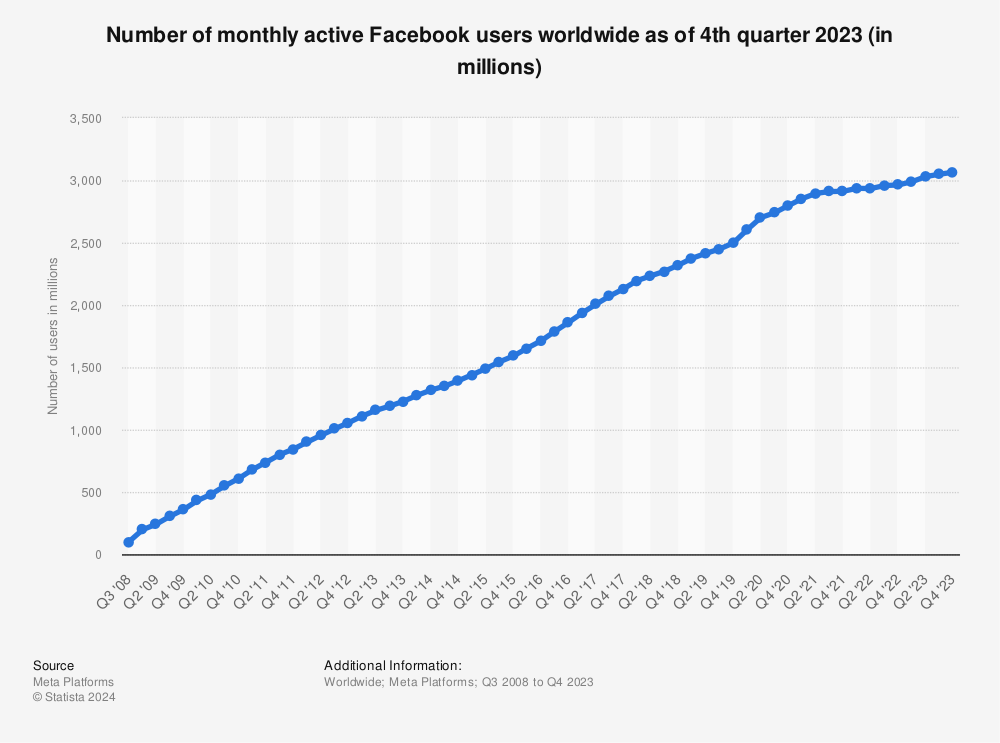

In his book True Enough, published in 2008, journalist Farhad Manjoo drew on the spread of imagery and conspiracy theories that followed 9-11 to ring an early bell on the dangers of digital echo chambers, political self sorting, and the spread of misinformation online. Remember, Manjoo was writing only 2 years after Facebook opened to the general public and Twitter first launched. Take a look at Facebook’s user growth in the decade since.

Find more statistics at Statista

That’s a 2,600% increase in potential spreaders since Manjoo worried about misinformation in digital spaces. Of course, we’re seeing more fakes news now!

Subjective Truth & Human Bias

The reason that viral content spreads so easily is that it exploits fundamental elements of our psyche and community loyalties. Rather than critically evaluate claims and sources, sharers of viral content and conspiracy theories are often responding emotionally or signaling their group membership.

A study in the journal Cognition in 2018 found that when asked to think critically about headlines, people could actually discern accurate headlines from fake ones, regardless of the ideological slant of the story. The authors conclude that when we share fake news, we’re most likely just not thinking critically about the content. To quote the authors, “susceptibility to fake news is driven more by lazy thinking than it is by partisan bias per se” (emphasis mine).

In 2017, researchers explored the role of emotion in the dissemination of information through social networks. They found that when social media content included emotion-inducing language or framed an issue in moral terms, it was much more likely to spread within an ideological group.

There’s a ton more work out there investigating why we share false claims. But in essence, when we have a motivating reason, like an emotional connection to the issue, a desire to support our “team”, or even just a moment of outrage, we simply don’t care whether it’s true or not. We may have the ability to critically evaluate the claims, but we lack the motivation to do so.

What to Do

There are plenty of suggestions out there for how to force social platforms to regulate themselves. While I think some of those are good ideas, the fact remains that social platforms are only the medium. I do think it’s true that Youtube’s algorithm should not push users towards polarizing content, and social platforms should bear some responsibility for policing the most inaccurate claims, especially when they’re weaponized. With the dawn of deep fakes, we’re in for a world of hurt if we don’t get our arms around this.

But it’s important to note that it’s us users who are doing the spreading. One of my favorite proposed solutions would be to force social media users to read articles before sharing them. As shown above, when we’re forced to slow down and think critically about sources and claims, we are still capable of sorting out the very worst.

So I challenge you, reader, to be a critical consumer of online media and selective sharer of “facts”. The American Press Institute offers 6 critical questions for evaluating content.

- What kind of content is this?

- Who and what are the sources cited and why should I believe them?

- What’s the evidence and how was it vetted?

- Is the main point of the piece proven by the evidence?

- What’s missing?

- Am I learning every day what I need?

Whether you like it or not, we live in a world of online content and competing realities. If facts have become negotiable, we have responsibility for which facts we choose. As I’ve written in the past, there are charlatans peddling the same snake oil that we’ve seen for generations. Only today, their reach is much expanded.

The average social media user spends upwards of 2 hours on social platforms every day. And research suggests that seeing false claims frequently, even if we’re not the ones sharing them, can make them seem more true.

The battle for truth is only getting started, and we’re each on the front lines. It will take a concerted effort from all of us to think critically about the information we’re consuming, support reputable writers and sources, and hold our emotional responses in check when choosing what to share.

As technology and our culture change rapidly, the knee jerk emotional reactions and social group signaling that comes so naturally to us need to change as well. It may be hard work, but as global citizens and the guardians of our future, it’s also our responsibility.